Part 1:

Ever since I was old enough to realize I was located within it, it’s been my prerogative to make my life about space. And here in college, I decided at least, in some adjacent way as a real estate development major, to pick up a degree in it. And aside from living and breathing space, when I look back upon my academic career I have realized that all this time, I have been writing about space as well.

In this paper, I want to examine 5 bodies of work I have written in college about space how they have affected me, and how my life, in turn, has affected them. They are all works of different genres, all for different classes with different goals. They are archaeology research papers and exhibition reviews. They are policy prescriptions, neighborhood analyses, and investment memorandums. They are intertwined with the unseen forces that shape our world: history, social contexts, law, and economics. So although I am characterized as unfocused at times in the subject matters I find interesting, or the classes I take, when I look at the body of writing I have completed so far now, I see a paper trail of this common denominator and the adventures I have had learning about various subjects along the way.

I consider myself to be one of the lucky ones, to have an interest that is so all-encompassing and adjacent to others. I am lucky enough to like what I am writing about 95% of the time. The exigencies of academia rarely phase me in this way. However, when I first entered college, I did not think that this would be enough to propel me through. After all, I entered college remotely during the pandemic and was in a major that, although utilized critical thinking and involved spatial elements, I hated. This major was architecture. Although it should have been the perfect fit for me, I couldn’t handle the perfect cuts, precision, and hours of gluing and model-making it required. In fact, I found myself much rather wanting to write about it.

The first paper I ever truly loved in college was called ‘Lhasa Built Environment Archaeological Project: Changes in Sacred Space’. This was a project that followed rules I should have hated. I had to follow research guidelines, a rigorous drafting process, craft my research question, and more. This paper examined how spiritual spaces’ use in Tibet’s capital has changed over time pre and post-invasion and was for an anthropology GE. During the process of writing this paper, I discovered two enduring aspects of my writing career. Firstly, I realized the joy of conducting research in the USC library. Secondly, I recognized my tendency to become deeply engrossed in my research, often to the point of blocking out the external world. This intense focus allowed me to explore topics that genuinely intrigued me, even amidst a worldwide pandemic or while taking unrelated courses.

Although I may not have enjoyed it to the fullest, my experience in architecture taught me valuable skills in working with multimedia, which I applied to answer the research question in my archaeology paper. Here, I relied on various sources, including oral histories, economic and population data, government policies (laws and city master plans), and medical journals from USC Libraries. In essence, I became a hunter-gatherer of information, piecing together a complex narrative from a wide range of sources.

This paper reinforced the timeless adage, "It's not about the destination; it's about the journey." This sentiment leads me to the significance of my subsequent paper, an exhibition review of Yoshitomo Nara's retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). I composed this review during my sophomore year while taking an art history General Education course that required students to write an exhibition review of an in-person visit.

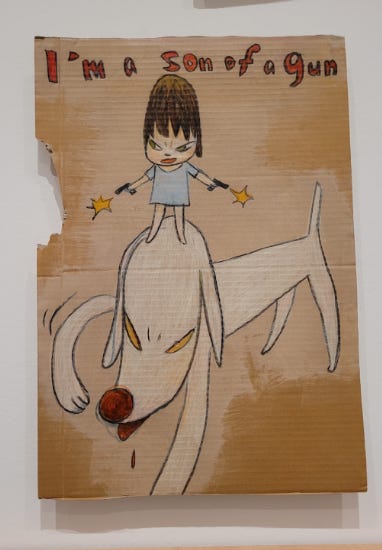

Choosing Yoshitomo Nara as the subject of my review was driven by my fascination with his illustrations, which I had encountered frequently on social media. Additionally, my interest in the impact of American colonialism on post-World War II Japan, explored in a class documentary, motivated me to select this particular artist for analysis. Initially, I expressed concerns in my review about my relationship with Nara's work being limited to his role as a contemporary pop culture and Superflat art movement icon. However, it was only when I visited the exhibition in person that I fully grasped the reasons behind Nara's distinctive artistic style. Observing the retrospective's curation, and chronological arrangement, and immersing myself in American folk music while exploring the gallery allowed me to understand the depth and complexity of his work. Recently, I noticed a Yoshitomo Nara sticker on someone's laptop, featuring a cutesy little figure of a girl. This encounter reminded me that my visit to the gallery two years ago had enabled me to appreciate the art on a profound level that transcended its superficial appeal.

But not all of my journeys had to be as glamorous as the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. In fact, the rest of the writing that I am most passionate about appears to be mundane on the surface and requires the most mundane journeys of all; through the stiffness of numbers and figures, and bureaucracy. To do this, I find myself most often in-person at the International Relations Library to get the good stuff, the prints you can’t read online.

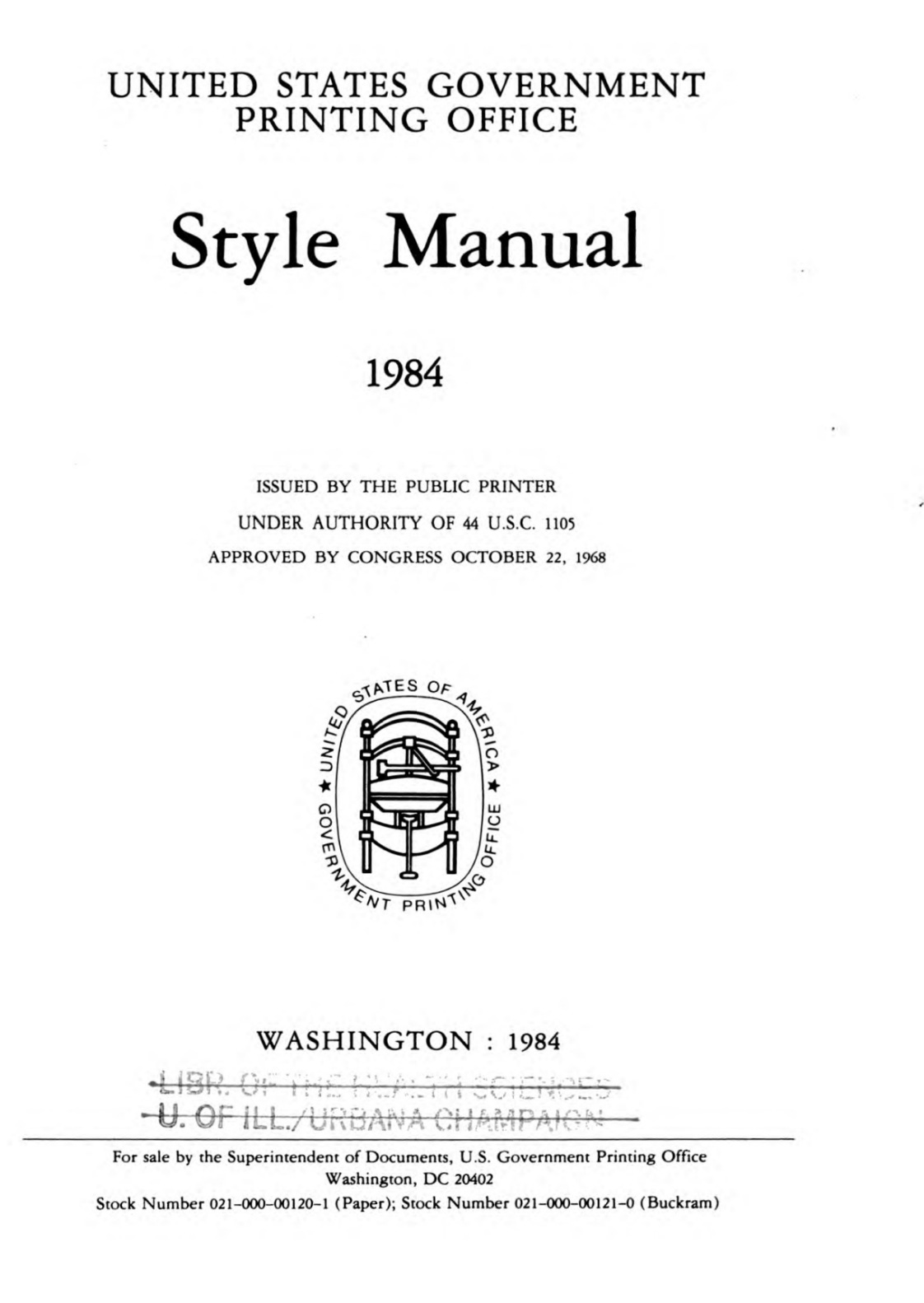

This extends back to my purpose at this school as a Real Estate Development Major. I look at policy and finance and how they shape space. In my Housing and Community Development course I took as an elective for my major last year we were tasked with a series of Housing and Community Development Reports on topics such as the Community Reinvestment Act and Opportunity Zones. Without my trips to the library in person, I would have easily been bored. It’s just something about an 80s serif governmental print (I seriously love those fonts) and flipping through tax credit manuals that makes me feel like a detective. I’m looking at something physical that others have before me, and for my HCD reports I always brought one of my good friends and classmates along. It’s a shared experience and makes my research all the more enjoyable.

I often have just as much fun connecting the dots for these more ‘mundane’ genres as well because they are directly applicable to my life. For example, in my real estate classes, we often write investment memos on properties we underwrite as exercises. In one of these memos my junior year I underwrote an 8-unit apartment complex on Melrose that I had often seen before. As a result of it being a real place, I felt a real stake in analyzing the market and supporting my assumptions on why someone should invest in it.

Clearly, I am not above genre conventions, but I try my best not to let them limit me. There is something about each genre in their own way that makes them special even with the common denominator of space. In all works, I utilize some form of additional media like in my archaeology research (like maps, images, and data tables). I like to experience things as they are or as they were in person as with the exhibition review and policy reports. And I like to relate them to the present or past as with my investment memos. Writing thus far, then, has been a loosely connected, spatiotemporal adventure.

PART 2

One particular piece of writing that stands out in my body of work is a travel guidebook I made for an elective architecture class during the spring term of my sophomore year. In "Architecture: People, Places, and Culture: Architecture of the Public Realm," we were tasked with examining Los Angeles specifically and how the architecture of different neighborhoods in the city interacted with the public. My final project, titled "Little Tokyo: A Scrapbook of Competing Interests, Recollection, Reality, and the Reality of the American Dream," was a culmination of my fusion of academic interest in space and my burgeoning passion for analysis, history, and economics.

The guidebook, in particular, was intended for a complete stranger. If hypothetically, my guidebook were found on the street of East First Street, I would want the passerby who picks it up to feel compelled to keep exploring Little Tokyo, to pass by its landmarks and businesses, and observe the actions of its residents with the help of the context I have provided.

As a guidebook, I was also no longer bound by the rigidity of academic conventions. I utilized in-person photography and data collection by walking through the neighborhood itself, much like how I took photos for my exhibition review. I utilized the archival images from the Los Angeles Italian American Museum, Los Angeles' Public Library Photo Collection, and KCET public radio, similar to how I performed for archaeological research. I drew from Los Angeles city planning documents and maps as I would for policy prescriptions to delineate the neighborhood's boundaries over time. Lastly, and most excitingly, in dealing with a project that had a real-life relation to me, I talked with the people who had a direct hand in shaping the public architecture of Little Tokyo itself.

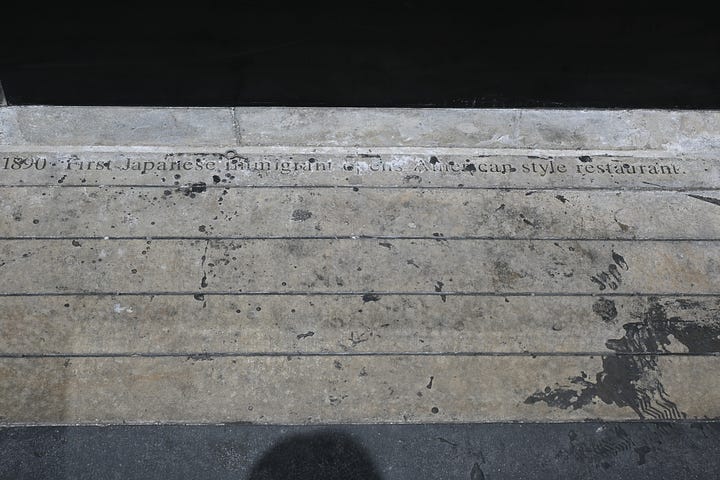

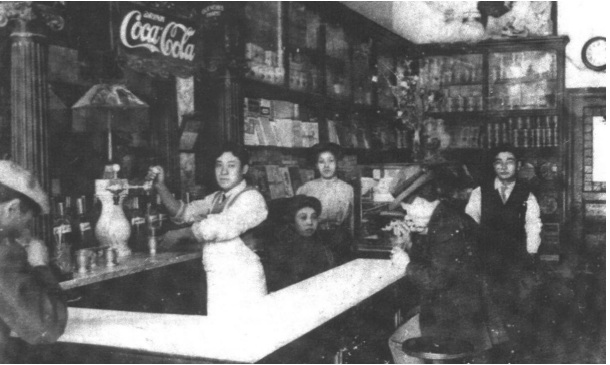

One of my most significant experiences was interviewing Bill Watanabe, who founded the Little Tokyo Service Center in the 1960s. I found Bill through reporting on the walking tours he has held through Little Tokyo for decades. The insights he shared with me provided crucial context that helped thread a journey through space. For example, in terms of culture, I noticed that Little Tokyo was focused on protecting its collective memories. Through Bill, I learned how thousands of interviews of residents were collected about their time in Little Tokyo prior to WWII to create a commemorative sidewalk display. Upon further investigation, I discovered the beauty of images that represented to the public what happened in the same adjacent buildings a hundred years before. I also learned about how the Little Tokyo Service Center protects its seniors by having created a housing trust to ensure residents have a place to live. In terms of places, the Little Tokyo Service Center was the first to begin preserving buildings that once were the cornerstone of first-generation and second-generation Japanese communities.

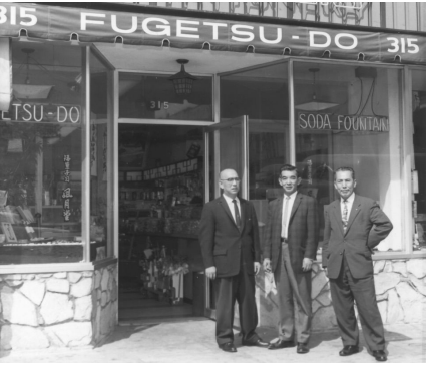

And thus, my project became less about space and more about cultural studies and urban history. It was about the identity of the neighborhood's residents evaluated through the lens of the book’s three-part structure. For example, through the lens of heritage vs. consumption, I took a look at how Walmart's most prolific mochi ice cream brand, My Mochi, actually originated here in Los Angeles as a 111-year-old store in Miyakawa before it closed during the pandemic. I got to see the pride of the great-grandchildren of desert shop owner Seiichi Kito in their 119-year-old business from the news clippings the shop had. I wanted my readers to feel the same way I did when I found that this unassuming shop stems from the effort of this patriarch who, even through internment, made his desserts through rations offered to him by other prisoners who wanted something that reminded them of home.

Recalling these feelings of bewilderment and discovery, I find that I would rather axe any effort to assign any sort of subject matter to what this piece of writing does. It's similar enough to my other works in that it includes an analysis of things I find interesting. Would it be enough to say that I have performed research on facets of this neighborhood that I found compelling and wanted to show to others? Of the beauty of persistence? My scrapbook may have a table of contents, but it would be just as well as a series of scraps as fragmented as memory itself. I think that I wanted it to be as absurd and anecdotal as a mirror of real life. Page 36 of the guidebook ends in this chaotic manner, by describing the re-planting of a 150-year-old grapefruit tree called Sunny.